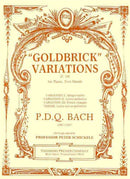

| 作曲者 | P.D.Q. Bach (1807-1742) |

| タイトル | Goldbrick Variations |

| サブタイトル | For Piano, Two Hands |

| 出版社 | Theodore Presser・プレッサー |

| 楽器編成 | Piano,ピアノ |

| 楽器編成(詳細) | Piano |

| 品番 | HL9781598067033 |

| 校訂者 | Prof. Peter Schickele |

| 形状 | 12 ページ・24.1 x 30.5 cm |

| 演奏時間 | 6:00 |

| 出版年 | 1996年 |

| 出版番号 | 110-40706 |

| ISBN | 9781598067033 |

The discovery of the “GOLDBRICK” VARIATIONS was an especially important one for a couple of reasons, both of them important. In the first place, it is a theme with variations, and P.D.Q. Bach’s use of this very usual eighteenth-century form was unusually unusual. And this piece is no exception. Because usually, when a composer writes a theme and variations, he presents the theme first, and then the variations. You sort of get used to that. Well, not P.D.Q. Bach. He presents all three variations first and only then does he get around to presenting the theme. I think the reason for this is that in this case even P.D.Q. realized that after hearing this theme nobody was going to stick around for the variations.

It was also an important discovery because very little of P.D.Q.’s solo piano music has survived. But there is more now than there was before the discovery of this piece, which is one of the things that makes it so important.

As was often the case, P.D.Q. tried in this work to emulate, or cash in on, the success of one of his father’s most important pieces, the aria with thirty variations written for a keyboard guy named Goldberg to play when his employer couldn’t sleep.

In Johann Sebastian’s masterwork, every third variation is canonic, that is, a second melodic part does exactly the same thing as the first melodic part, except starting later and on a different note, while the first part blithely proceeds with new stuff, which, of course, the second part then has to imitate later and on different notes, so you’d think it would sound pretty awful, but it doesn’t, it sounds just fine. All this happens over a free bass line (Bach lived long before free-basing was made illegal).

Since P.D.Q. Bach only wrote three variations altogether, there is only one canonic one, which is the middle one, and the artistically short-changed progeny of the Leipzig master exhibited his cleverness not in counterpoint, but in his masterful avoidance of it, that is, every time the second melodic part comes in, the first part has rests, and vice versa. Were the two melodic parts the only parts, the resulting texture would barely, and only occasionally, earn the description “contrapuntal;” fortunately, here too, there is a free bass line which acts as musical cornstarch.

Variation I

Variation II

Variation III

Theme